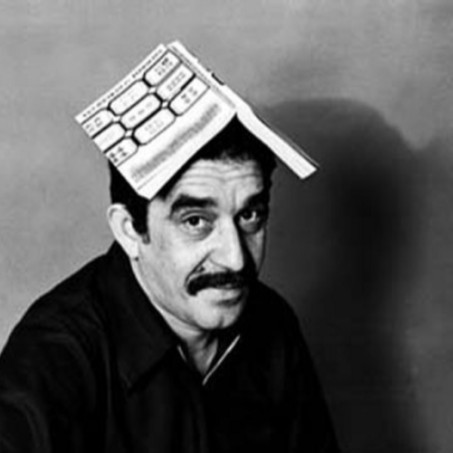

Mi profesora de literatura contemporanea aqui, Pfa. Milagros del Castillo, había mencionado en clase la "joya" que Gabriel García Márquez les había traído de Colombia a Salamanca cuando vino a dar una charla alli hasta una decada, y me inspiro a leerlo y hacer una traducción a ingles. Espero que les inspire tambien.

Elijah Anderson Barrera

Publicada por la primera vez en

La Jornada, México, 8 de abril de 1999.

A mis doce años de edad estuve a punto de ser atropellado por una bicicleta. Un señor cura que pasaba me salvó con un grito: ¡Cuidado! El ciclista cayó a tierra. El señor cura, sin detenerse, me dijo: ¿Ya vio lo que es el poder de la palabra? Ese día lo supe. Ahora sabemos, además, que los mayas lo sabían desde los tiempos de Cristo, y con tanto rigor, que tenían un dios especial para las palabras.

At twelve years old I was almost run over by a bicycle. A passing priest saved me by shouting: “Look out!” The cyclist fell to the ground. The priest, without stopping, said: “Can you see how powerful words are?” That day I found out. Now we know that the Maya had known about this power since the time of Christ. They were so rigorous about it, in fact, that they had a special god just devoted to words.

Nunca como hoy ha sido tan grande ese poder. La humanidad entrará en el tercer milenio bajo el imperio de las palabras. No es cierto que la imagen esté desplazándolas ni que pueda extinguirlas. Al contrario, está potenciándolas: nunca hubo en el mundo tantas palabras con tanto alcance, autoridad y albedrío como en la inmensa Babel de la vida actual. Palabras inventadas, maltratadas o sacralizadas por la prensa, por los libros desechables, por los carteles de publicidad; habladas y cantadas por la radio, la televisión, el cine, el teléfono, los altavoces públicos; gritadas a brocha gorda en las paredes de la calle o susurradas al oído en las penumbras del amor.

Never before has the power of the word been as powerful as it is today. Humanity enters the third millennium under the reign of words. It’s not true that the image is displacing the word, or it will become extinct. On the contrary, they are becoming empowered: the world never had many words with so much scope, authority, and will as there is in the great Babel of modern life. Invented words, condemned or sanctified by the press, in disposable books, on the advertizing billboards, spoken and sung on the radio, television, in the movies, over the telephone, across public speakers, shouted with a broad brush on the walls of the street or whispered in the ear among the shadows of love.

No: el gran derrotado es el silencio. Las cosas tienen ahora tantos nombres en tantas lenguas que ya no es fácil saber cómo se llaman en ninguna. Los idiomas se dispersan sueltos de madrina, se mezclan y confunden, disparados hacia el destino ineluctable de un lenguaje global.

No. The defeated one is silence. Things now have so many names in so many languages that it’s not easy to know what they're called anywhere. Languages wander like orphans, mix and mingle, propelled toward the inevitable fate of a single global language.

La lengua española tiene que prepararse para un ciclo grande en ese porvenir sin fronteras. Es un derecho histórico. No por su prepotencia económica, como otras lenguas hasta hoy, sino por su vitalidad, su dinámica creativa, su vasta experiencia cultural, su rapidez y su fuerza de expansión, en un ámbito propio de diecinueve millones de kilómetros cuadrados y cuatrocientos millones de hablantes al terminar este siglo. Con razón un maestro de letras hispánicas en los Estados Unidos ha dicho que sus horas de clase se le van en servir de intérprete entre latinoamericanos de distintos países. Llama la atención que el verbo pasar tenga cincuenta y cuatro significados, mientras en la república del Ecuador tienen ciento cinco nombres para el órgano sexual masculino, y en cambio la palabra condoliente, que se explica por sí sola, y que tanta falta nos hace, aún no se ha inventado. A un joven periodista francés lo deslumbran los hallazgos poéticos que encuentra a cada paso en nuestra vida doméstica. Que un niño desvelado por el balido intermitente y triste de un cordero, dijo: «Parece un faro». Que una vivandera de la Guajira colombiana rechazo un cocimiento de toronjil porque le supo a Viernes Santo. Que Don Sebastián de Covarrubias, en su diccionario memorable, nos dejó escrito de su puño y letra que el amarillo es el color de los enamorados. ¿Cuántas veces no hemos probado nosotros mismos un café que sabe a ventana, un pan que sabe a rincón, una cereza que sabe a beso?

The Spanish language has to prepare for the next great cycle in a future without borders. It is a historical mandate. Not because of its economic value, but for its vitality, its dynamic creativity, its vast experience culture, its speed and force of expansion in its own sphere of nineteen million square kilometers which contained four million speakers by end of the twentieth century. No wonder a master of Hispanic literature in the United States has said that his hours of class will serve him best as interpreter between speakers from different Latin American countries. It is noteworthy that the verb pasar has fifty-four meanings, while in the Republic of Ecuador there are a hundred and five names for the male sexual organ, and that the word condoliente, which is self-explanatory (*co-sufferer), which is a word we need so badly, has not yet been invented. A young French journalist was dazzled by the poetry that he found at every step in the language of our domestic life. A child touched by the intermittent and sad bleating of a sheep, once said: Parece un faro "It’s like a lighthouse." That a woman selling vegetables in the Colombian Guajira market rejected a sprig of Lemon Balm because it tasted of Good Friday. That Don Sebastian de Covarrubias, in his memorable dictionary, set down in his own hand that yellow is the color of love. How many times have we sipped coffee that tastes like a window, bread that tastes like a our favorite corner, or a cherry that tastes like a kiss?

Son pruebas al canto de la inteligencia de una lengua que desde hace tiempos no cabe en su pellejo. Pero nuestra contribución no debería ser la de meterla en cintura, sino al contrario, liberarla de sus fierros normativos para que entre en el siglo veintiuno como Pedro por su casa.

This is all proof of the intelligence and creativity of a language that for a long time now has not fit in its own skin . But our contribution should not be putting it in a girdle, but instead, to free it from its regulatory braces so it can enter the twenty-first century as St. Peter enters his own domain.

En ese sentido, me atrevería a sugerir ante esta sabia audiencia que simplifiquemos la gramática antes de que la gramática termine por simplificarnos a nosotros. Humanicemos sus leyes, aprendamos de las lenguas indígenas a las que tanto debemos lo mucho que tienen todavía para enseñarnos y enriquecernos, asimilemos pronto y bien los neologismos técnicos y científicos antes de que se nos infiltren sin digerir, negociemos de buen corazón con los gerundios bárbaros, los ques endémicos, el dequeísmo parasitario, y devolvamos al subjuntivo presente el esplendor de sus esdrújulas: váyamos en vez de vayamos, cántemos en vez de cantemos, o el armonioso muéramos en vez del siniestro muramos. Jubilemos la ortografía, terror del ser humano desde la cuna: enterremos las haches rupestres, firmemos un tratado de límites entre la ge y jota, y pongamos más uso de razón en los acentos escritos, que al fin y al cabo nadie ha de leer lagrima donde diga lágrima ni confundirá revolver con revólver. ¿Y qué de nuestra be de burro y nuestra ve de vaca, que los abuelos españoles nos trajeron como si fueran dos y siempre sobra una?

To this end, I boldly suggest to this wise audience that we simplify the grammar before the grammar simplifies us. Let’s humanize its rules, and let’s learn from indigenous languages all they have still to teach and enrich us, we’ll assimilate quickly and well the technical and scientific neologisms before they infiltrate us and get out of control, let’s negotiate in goodheartedly with barbaric gerunds, the endemic word que, and the parasitic use of dequeísmo (the use of the grammatical constriuct de que instead of simply que), and return the present subjunctive the splendor of their proparoxytone: váyamos(let’s go) instead of vayamos (we go), cántemos(let’s sing) instead of cantemos (we sing), or the harmonious muéramos (let’s die together) instead of the sinister muramos (we die). Let’s retire spelling,which terrorizes human beings from the cradle: and let’s bury the useless letter H, sign a border treaty between G and J, and put more logic into the use of accents, which after all no one is likely to read lagrima where it says lágrima (tear) nor confuse revolver(to spin) with revolver (a handgun). And what about our letter B as in burro and our V as in vaca, that our Spanish grandparents brought to us as if two and two always made one?

Son preguntas al azar, por supuesto, como botellas arrojadas a la mar con la esperanza de que le lleguen al dios de las palabras. A no ser que por estas osadías y desatinos, tanto él como todos nosotros terminemos por lamentar, con razón y derecho, que no me hubiera atropellado a tiempo aquella bicicleta providencial de mis doce años.

These are random questions, of course, like bottles thrown in the sea with the hope that they will somehow make their way to the god of words. If not for this daring and folly we would all end up lamenting, and rightly so, that I hadn’t been run over at the age of twelve by that providential bicycle.

Gabo: Una Vida