Cuando tenía 5 años, jugaba con lodo, pateaba cosas redondas, y asistía a una escuela preescolar en el Valle de San Fernando que se llamaba ‘la Granjita’ (Farm School). Aunque mis recuerdos de este lugar son vagos, yo definitivamente no tengo ningún recuerdo de haber sido evaluado de ninguna manera. Tengo un recuerdo brumoso de haber recibido golpecitos por las cabras y haber montado una tortuga gigante. En general, recuerdo que lo había pasado muy bien allí.

El próximo año, ya estaba listo para una nueva escuela-una escuela académica. Un día mi madre me llevó hasta Mulholland Drive a un lugar llamado la escuela Mirman para tomar una prueba en su camioneta antigua “Town and Country” con paneles de madera falsa. Me senté en la oficina de uns psicóloga educativa llamado Dr. Vaughan que me mostró una serie de formas y después me dijo: "vamos a jugar." Cuadrado-círculo-cuadrado-triángulo-cuadrado ... ¿cuál sería la próxima forma? Y yo elegí. Ummmm ... círculo. Ella no dijo nada, pero metió la mano bajo la mesa y sacó otro juego y luego jugamos otro “juego” ...

No lo sabía en ese momento, pero este juego resultó ser una prueba de inteligencia. Pasé su mínimo requisito de coeficiente intelectual (IQ) de 145 (supuestamente una nivel de altas capacidades intelectuales), y me matricule en la escuela. Como resultado, la escuela estaba llena de los descendientes de los inteligentes (Carl Sagan, etc) y los famosos (Helen Reddy, etc) A pesar de ser un lugar que alienta la creatividad y la compasión, la escuela necesariamente se definía por los caprichos de la prueba de Binet, y nadie se olvidó de que estaban allí porque habían recibido una ración extra de espagueti en la cafetería de su nacimiento.

Para mí, en ese entonces, la inteligencia era un don (de ahí la palabra donato) que se había parcelado el destino y que se mantuvo una cantidad estática hasta el final de la vida. 37 años de experiencia al contrario (por ejemplo, las tres horas que pasé buscando las llaves del coche que estaban siempre encima de la mesa) ha desestabilizado la solidez de esta creencia un poco. Ahora, esta creencia ha sido totalmente vencido con mi lectura del libro “Mindset: la nueva psicología del éxito (¿cómo podemos aprender a realizar nuestro potencial)” de Carol Dweck.

Un tema del libro es que nuestras creencias de cómo estática o elásticos son nuestras habilidades pueden tener un efecto enorme sobre nuestros logros y crecimiento. Para Dweck, nuestras capacidades no son ni completamente la naturaleza (145 IQ por vida), ni la crianza (tener una madre con doctorado que le gustaba leerme cuentos) ni el ambiente natural (cabeceras de con pelotas demasiado infladas en los días invernales). Más bien, nuestra capacidad (intelectual, social, atlético) es el resultado de una compleja interacción entre todos estos elementos.

Todos empezamos con un puño de naipes, pero la manera en que desempeñamos esas tarjetas importa mucho. En el libro la autora cita a Alfred Binet, el inventor de la prueba de IQ que en realidad no creía en una inteligencia "fija". Binet dijo que las personas que comienzan los más inteligentes terminan asi. Del mismo modo, Robert Stineberg señaló que el logro "La habilidad no es fija, pero se desarrolla con la esfuerza con propósito." El puño de naipes del nacimiento para Dweck es "sólo el punto de partida para el desarrollo”. De hecho, la manera en que nos vemos a nosotros mismos (nuestra manera de pensar) es lo que más determina el resultado de nuestros esfuerzos.

Dweck presenta dos tipos “Mindset” (formas de pensar), el “Mindset” fijo y el “Mindset” de crecimiento. El “Mindset” fijo dice: Tengo X cantidad de capacidad, más vale defender este concepto establecido y probarlo en un ambiente seguro y evitar situaciones que pudieran revelar mis insuficiencias (si no se arriesga nada, nada se pierde). Al contrario, el “Mindset” de crecimiento dice: los retos me estiran y me mejoran, porque mis cualidades no son de una cantidad fija, y me abro a pas posibilidades de aprender y a hacer un cambio positivo (si no se arriesga, no gana nada).

Las personas con un “Mindset” de crecimiento son participantes activos en la creación de su propia capacidad en lugar de simplemente sufrir los efectos de esas habilidades. El “Mindset” de crecimiento responde a los estímulos negativos con una actitud de desarrollo y cambio, listo para enfrentar los desafíos que le presenta la vida (a través del proceso de crecimiento y mejoramiento de sí mismo-el aprendiz).

Por el otro lado, el “Mindset” estática responde a victoria exageradamente (a través de un ego que juzga a otros como menos) o la admisión de la derrota completa (acompañada de un ego desinflado-imaginando que a otros juzgan a el-que no aprende). El “Mindset” estática atributa cada victoria o cada derrota a la bodega de la capacidad finita. Mientras el “Mindset” de crecimiento sabe que el aprendizaje siempre es posible, que el desarrollo es un placer, y que el almacén es una ilusión.

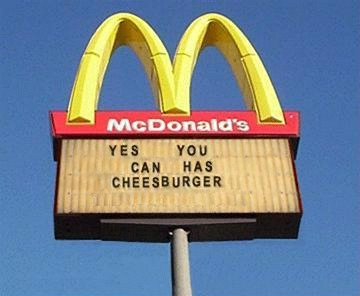

En la India? Come en el McDonalds. Japón? McDonalds. Para el “Mindset” fijo, se sabe que la comida Big Mac está siempre disponible, y no es necesario modificar sus paradigmas. El esfuerzo de aprender cosas nuevas es demasiado arriesgado. Cuando seguimos un curso prescrito, existe poco riesgo, y el mundo parece estar en orden completo. Pero en realidad...

¿Para qué viajamos si queremos vivir las mismas sensaciones que experimentamos en casa? ¿Para qué vivir si uno repite los mismos rituales como un Sísifo contento?

En las relaciones, ¿queremos que nos pongan en un pedestal y que estemos adorados por nuestros rasgos estáticos? O ¿Preferiremos ponernos a pruebas y desarrollarnos a una persona mejor por aprender? Todo eso depende de su forma de pensar. ¿Quieres vencer todos los equipos en la liga por 5 goles o material de desecho y luchar por un empate 1-1. Todo depende de su forma de pensar.

Quiero concluir con unas palabras del gran poeta persa Rumi Jalalu'l-Din, que definitivamente tenía una mentalidad de crecimiento:

Este ser humano es una casa de huéspedes.

Cada mañana, un recién llegado.

Una alegría, una depresión, una mezquindad,

algo de conciencia momentánea viene

como una visita inesperada.

Dele el bienvenido y entretener a todos!

Incluso si viene una multitud de dolores,

que violentamente barren su casa

vacía de todos sus muebles,

todavía trátalo a cada huésped con honor.

Puede ser que te están despejando para un placer nuevo.

El pensamiento oscuro, la vergüenza, la malicia,

reúnete con ellos en la puerta riéndote, e invitarlos a entrar

(De "La casa de huéspedes" - traducido a ingles por Coleman Barks, Baylor ex Alumno y de alli a castellano por Elijah Anderson Barrera 2010)

Becoming is better than Being: Mindset

When I was about 5, I played in the mud, kicked round objects, and attended a preschool in the San Fernando Valley called Farm School. Though my memories of this place are vague, I definitely don’t remember being assessed in any way. I have foggy memories of being butted by goats and riding a giant tortoise. Overall, I remember having a great time there.

A year or so later, I was ready for a new school—an academic school-- so my mother drove me up Mulholland Drive in her old Town and Country fuax-wood-paneled station wagon to a place called Mirman School to take a test. I sat in an office across the desk from an educational psychologist named Dr. Vaughan who showed me a series of shapes and said, “we’re going to play a game.” Square-circle-square-triangle-square… which comes next? And I chose. Ummmm… circle. She said nothing, but reached under the table and took out another game and then we played that…

I didn’t know it at the time, but this game turned out to be an IQ test. I passed somewhere above their minimum IQ requirement of 145 (highly gifted), and was admitted to the school. As it turns out, the school was littered with the offspring of the intelligent (Carl Sagan, etc.) and the famous (Helen Reddy, etc.) In spite of being a place that encouraged creativity and compassion, the school necessarily defined itself by the whims of Binet’s IQ test, and nobody ever forgot that they were there because they had gotten an extra helping of spaghetti at the cafeteria line of their birth.

For me, intelligence was a gift (hence the word gifted) that was parceled out and remained a static quantity up until the end of one’s life. 37 years of experience to the contrary (for example, the three hours I spent looking for the car keys that were on top of the dresser) has unsettled the solidity of this belief a bit. Now, this belief has been fully vanquished with my reading of

Mindset: the new Psychology of Success (how we can learn to fulfill our potential) by Carol S. Dweck.

A theme of the book is that our beliefs about how static or elastic our abilities are can have a huge effect on our achievement and growth. For Dweck, our abilities are neither completely nature (145+ IQ for life) nor nurture (having a mother with a PhD who likes to read bedtime stories) nor environment (many headers with overinflated balls on cold days). Rather, our ability (intellectually, socially, athletically) is a result of a complex interplay between all of these elements.

We all start out with a certain hand of cards, but the way we play those cards matters a great deal. The author cites Alfred Binet, the inventor of the IQ test who actually did not believe in a “fixed” intelligence. For Binet, it’s not always the people who start out the smartest that end up the smartest. Similarly, Robert Stineberg noted that achievement “is not some fixed prior ability, but purposeful engagement.” The hand that you are dealt at birth for Dweck is “just the starting point for development." In fact, the way we see ourselves (our mindset) is what most significantly determines the outcome of our efforts.

Dweck presents two kinds of mindset—the fixed mindset and the growth mindset. The fixed mindset takes the position: I have X amount of ability, I better defend this set concept by proving it in safe environments, and avoiding situations that might reveal my inadequacies (nothing ventured, nothing lost). The growth mindset takes the position: challenges will stretch me and improve me, because my qualities are not a fixed quantity but are in fact open to positive change (nothing ventured, nothing gained).

People with a growth mindset are active participants in the creation of their own ability instead of simply effects of those abilities. The growth mindset responds to negative stimuli with an attitude of growth and change, ready to confront the challenges that life presents (through the process of growth and self-improvement—the learner). On the other hand, the static mindset responds to challenge by ecstatically claiming victory (through an ego boost- judge others as lesser-nonlearning) or admission of defeat (accompanied by an ego deflation-imagining others to judge self as lesser-nonlearning). The static mindset attributes each victory or defeat to the storehouse of finite ability. The growth mindset knows that learning is always possible, that development is a pleasure, and that the storehouse is an illusion.

In India? Eat at McDonalds. Japan? McDonalds. For the fixed mindset, one knows that the big mac meal is always available, and one does not need to alter paradigms. Learning new things is too risky. When we follow a prescribed course, there is little risk involved, and the world seems to be in order. But really…why travel if we want experience the same sensations that we do at home? Why live if one repeats the same safe rituals like a contented Sisyphus?

In relationships do we want to be put on a pedestal and worshiped for our static traits, or challenged to be a better person and learn new things? That depends on our mindset. Do you want to beat every team in the league by 5 goals or scrap and fight for a 1-1 draw? That depends on your mindset.

I will close with a few words from the great Persian poet Jalalu’l-din Rumi, who definitely had a growth mindset:

This being human is a guest house.

Every morning a new arrival.

A joy, a depression, a meanness,

some momentary awareness comes

as an unexpected visitor.

Welcome and entertain them all!

Even if they are a crowd of sorrows,

who violently sweep your house

empty of its furniture,

still treat each guest honorably.

He may be clearing you out for some new delight.

The dark thought, the shame, the malice,

meet them at the door laughing, and invite them in.

(From “The Guest House” – translated by Coleman Barks, Baylor Alumnus)